Urban India’s push to build cleaner, healthier and more sustainable cities has brought household waste segregation into sharp regulatory focus. Across India’s Smart Cities and other urban centres, residents are legally required to segregate waste at source under national rules framed nearly a decade ago. These obligations are enforced through municipal bye-laws, door-to-door collection systems and, increasingly, monetary penalties for non-compliance. As city administrations strengthen enforcement, understanding the rules governing household waste segregation and the consequences of violations has become essential for urban residents.

Background: How waste segregation became a legal obligation

India’s modern urban waste management framework rests primarily on the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, notified under the Environment (Protection) Act. These rules replaced earlier regulations and marked a shift from landfill-centric disposal towards segregation, processing and resource recovery. For the first time, segregation of waste at source was made a mandatory duty for every waste generator, including individual households, apartment complexes, institutions and commercial establishments.

The rules were designed to address long-standing challenges in Indian cities, including overflowing landfills, open dumping, burning of waste and public health risks. By separating biodegradable waste from recyclables and hazardous household waste, authorities aimed to enable composting, recycling and safer disposal while reducing the burden on landfills.

Parallel national programmes such as the Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) and the Smart Cities Mission reinforced these objectives. Waste management became a core indicator of urban performance, linking cleanliness rankings, funding incentives and public accountability to segregation and processing outcomes.

The legal framework governing household waste segregation

At the national level, the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 establish the overarching legal framework. They define responsibilities for waste generators, urban local bodies, state governments and pollution control authorities. However, day-to-day enforcement depends largely on state municipal laws and city-specific bye-laws.

Urban local bodies are empowered to frame bye-laws specifying how segregation must be carried out, what infrastructure residents must use, how collection will be organised and what penalties apply for violations. As a result, while the core obligation to segregate waste is uniform nationwide, the operational details and penalty amounts vary from city to city.

This decentralised structure allows cities to tailor enforcement to local conditions but also leads to uneven awareness and compliance across urban India.

What households are required to segregate

Under the national rules, households must segregate waste into at least three broad categories before handing it over for collection. Biodegradable or wet waste includes kitchen waste, food scraps, fruit and vegetable peels and garden waste. Dry waste includes recyclable materials such as paper, cardboard, plastics, metals, glass and textiles. Domestic hazardous waste includes items such as used batteries, expired medicines, cleaning chemicals, paints, sanitary waste and e-waste.

Households are expected to store these categories separately and hand them over to authorised collectors as per the collection schedule notified by the municipality. Mixing segregated waste after collection is prohibited, and municipal authorities are required to ensure that segregated streams remain separate throughout transportation and processing.

In many cities, municipal bye-laws specify colour-coded bins or bags for different waste streams. Residents are expected to follow these instructions to ensure compliance.

Responsibilities of apartment complexes and housing societies

Large residential complexes and housing societies are treated as collective waste generators under the rules. Management committees are responsible for ensuring segregation at source within the premises and for coordinating with authorised collection agencies.

In many Smart Cities, housing societies generating waste beyond a specified threshold are classified as bulk waste generators. Such societies may be required to process biodegradable waste on site through composting or bio-methanation or to engage authorised service providers for decentralised treatment. Failure to comply can attract higher penalties compared to individual households.

Housing societies also play a key role in awareness building, infrastructure provision and monitoring compliance among residents, making them central to the success or failure of segregation efforts.

How Smart Cities operationalise segregation rules

Smart Cities have been positioned as demonstration grounds for modern waste management practices. Many have invested in door-to-door collection systems, GPS-tracked vehicles, material recovery facilities and decentralised composting units. Digital platforms are used to track collection, process grievances and monitor contractor performance.

Behavioural change campaigns form a significant part of Smart City waste strategies. These include door-to-door outreach, school programmes, community volunteers and mass communication campaigns aimed at normalising segregation habits. In some cities, compliance is incentivised through reduced user charges or public recognition, while non-compliance attracts fines.

Despite these efforts, performance varies widely. Some Smart Cities report high segregation rates and reduced landfill dependence, while others struggle with inconsistent collection, limited processing capacity and low public participation.

Penalties for non-segregation: what the rules allow

The Solid Waste Management Rules empower authorities to take action against violations, but they do not prescribe a uniform national fine for household non-segregation. Instead, penalties are imposed under municipal bye-laws framed by urban local bodies.

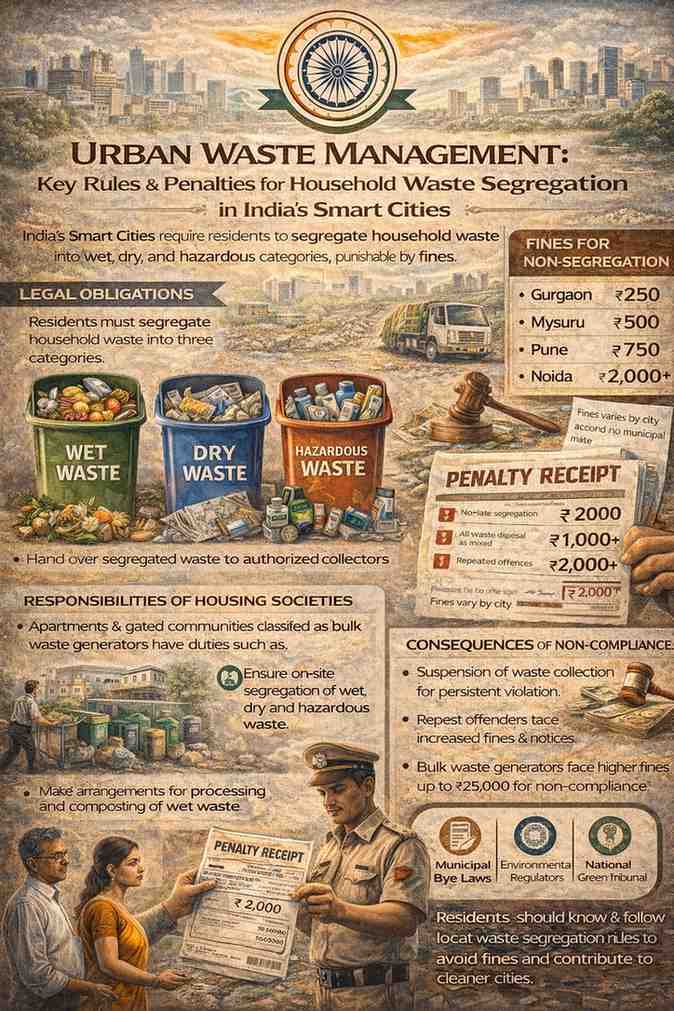

Typically, municipal bye-laws provide for on-the-spot fines for offences such as failure to segregate waste, littering, burning waste or dumping waste in public places. For individual households, fines often range from a few hundred rupees to a few thousand rupees per offence, depending on the city and the nature of the violation.

Repeat offenders may face higher fines, written warnings or, in some cases, suspension of waste collection services until compliance is ensured. For bulk waste generators, penalties can be significantly higher, reflecting the larger volume of waste and greater environmental impact.

Variation in penalties across cities

Penalty structures differ widely across Indian cities due to differences in municipal laws, administrative priorities and enforcement capacity. Some cities impose modest fines focused on behaviour correction, while others have adopted higher penalties to signal zero tolerance for non-compliance.

In metropolitan areas and planned cities, municipal corporations have announced substantial fines for housing societies, hotels, clubs and institutions that fail to segregate or process waste as required. These measures are often accompanied by inspections and public notices to deter violations.

At the household level, enforcement tends to be less punitive and more educational in many cities, particularly during early phases of implementation. However, as cities move from awareness to enforcement, residents are increasingly encountering monetary penalties for repeated non-compliance.

Role of environmental regulators and courts

Beyond municipal enforcement, environmental regulators and judicial bodies play a critical role in waste governance. State pollution control boards are responsible for monitoring compliance with waste management standards, particularly for processing and disposal facilities.

The National Green Tribunal has emerged as a key forum for addressing systemic failures in solid waste management. In several cases, the tribunal has directed municipal bodies to impose penalties, improve segregation, remediate dumpsites and submit time-bound action plans. While households are rarely direct parties before such forums, tribunal orders influence municipal enforcement strategies and underscore the legal seriousness of waste violations.

These interventions highlight that waste segregation is not merely a civic responsibility but a legal obligation linked to environmental protection.

Challenges in enforcing household segregation

Despite clear rules, enforcement at the household level faces practical challenges. Awareness gaps remain significant, particularly among new urban residents and migrant populations. Inconsistent collection schedules and lack of segregated transportation undermine public trust, leading residents to question the value of segregation.

Infrastructure limitations also constrain enforcement. In areas without sufficient processing capacity, segregated waste may still end up mixed or dumped, discouraging compliance. Staffing shortages and competing municipal priorities further limit routine monitoring.

As a result, many cities rely on periodic drives and selective enforcement rather than continuous oversight, leading to uneven outcomes.

Impact of penalties on citizen behaviour

Evidence from multiple cities suggests that penalties alone do not guarantee sustained segregation. While fines can prompt short-term compliance, long-term behavioural change depends on reliable services, clear communication and community engagement.

Where penalties are combined with consistent door-to-door collection, visible processing facilities and feedback mechanisms, segregation rates tend to improve. Conversely, punitive enforcement without service improvements often leads to resistance and informal disposal practices.

Smart Cities that have adopted phased enforcement, starting with warnings and awareness before imposing fines, generally report better public acceptance.

Economic and environmental implications

Effective household segregation has tangible economic and environmental benefits. Segregated biodegradable waste can be composted or converted to energy, reducing landfill volumes and methane emissions. Recyclable dry waste generates livelihoods for waste workers and reduces demand for virgin materials.

Conversely, failure to segregate increases processing costs, contaminates recyclables and accelerates landfill saturation. Municipal budgets bear the burden through higher transportation and disposal expenses, ultimately affecting taxpayers.

From a public health perspective, improved waste management reduces disease vectors, improves air quality by curbing burning and enhances overall urban liveability.

What households should do to comply

Households can avoid penalties and contribute to cleaner cities by understanding and following local segregation rules. This includes using designated bins, adhering to collection schedules and keeping hazardous household waste separate. Residents should also stay informed about municipal notifications and updates, particularly regarding changes in collection systems or enforcement practices.

In apartment complexes, cooperation with management committees and participation in community initiatives can help resolve practical issues and ensure compliance at scale.

The role of citizen engagement and accountability

Sustained success in waste segregation depends on shared responsibility. Municipal authorities must deliver reliable services and transparent enforcement, while citizens must adopt segregation as a routine habit rather than a temporary obligation.

Public reporting mechanisms, grievance redressal systems and community monitoring can strengthen accountability on both sides. In Smart Cities, digital platforms increasingly enable residents to report missed collections, illegal dumping and non-compliance, reinforcing collective oversight.

Future direction of urban waste regulation

Looking ahead, policy emphasis is expected to shift further towards circular economy principles. Extended producer responsibility regimes for plastics and packaging, stricter landfill norms and decentralised processing are likely to influence how segregation rules evolve.

For households, this may translate into additional segregation requirements or take-back systems for specific waste streams. Penalties may also be rationalised to ensure fairness while maintaining deterrence.

Conclusion

Household waste segregation in India’s Smart Cities is no longer optional; it is a legally enforceable requirement rooted in national environmental policy. While penalties for non-compliance vary across cities, the underlying obligation is uniform and increasingly enforced.

For urban residents, understanding segregation rules and local bye-laws is essential to avoid fines and contribute to cleaner neighbourhoods. For municipal authorities, the challenge lies in balancing enforcement with service delivery and public engagement.

Ultimately, effective urban waste management depends less on penalties alone and more on building systems that make segregation easy, reliable and socially accepted. As India’s cities continue to grow, the success of waste segregation will remain a key indicator of urban governance and environmental responsibility.

Add newspixel.in as preferred source on google – click here

Last Updated on: Thursday, January 29, 2026 12:21 pm by News Pixel Team | Published by: News Pixel Team on Thursday, January 29, 2026 12:21 pm | News Categories: News

Comment here